Dr Willie Soon and Dr. William Briggs

Global-warming fanatics take note - Sunspots do impact climate From the The Washington Times - By Willie Soon and William M. Briggs

Scientists have been studying solar influences on the climate for more than 5,000 years.

Chinese imperial astronomers kept detailed sunspot records. They noticed that more sunspots meant warmer weather. In 1801, the celebrated astronomer William Herschel (discoverer of the planet Uranus) observed that when there were fewer spots, the price of wheat soared. He surmised that less light and heat from the sun resulted in reduced harvests.

Earlier last month, professor Richard Muller of the University of California-Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature (BEST) project announced that in the project’s newly constructed global land temperature record, “no component that matches solar activity” was related to temperature. Instead, Mr. Muller said carbon dioxide controlled temperature.

Could it really be true that solar radiation - which supplies Earth with the energy that drives our climate and which, when it has varied, has caused the climate to shift over the ages - is no longer the principal influence on climate change?

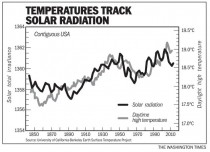

Consider the accompanying chart. It shows some rather surprising relationships between solar radiation and daytime high temperatures taken directly from Berkeley’s BEST project. The remarkable nature of these series is that these tight relationships can be shown to hold from areas as large as the United States.

This new sun-climate relationship picture may be telling us that the way our sun cools and warms the Earth is largely through the penetration of incoming solar radiation in regions with cloudless skies. Recent work by National Center for Atmospheric Research senior scientists Harry van Loon and Gerald Meehl place strong emphasis on this physical point and argue that the use of daytime high temperatures is the most appropriate test of the solar-radiation-surface-temperature connection hypothesis. All previous sun-climate studies have included the complicated nighttime temperature records while the sun is not shining.

Read more: SOON AND BRIGGS: Global-warming fanatics take note - Washington Times

See an older story here.

In addition to the declining net worth for the middle class under Obama (4.8% in the last 3 1/2 years up from 2.6 in the Dodd Frank housing bubble recession of 2007-2009) and large increases in health care (my provider already warned of 22-25% increases in 2013), we are about to take a devastating hit from the green agenda (hidden in the first term because of the potential outrage by the low and middle class but promised with a wink and a nod to the greens. These are considered despite the fact these same green policies have proved a dismal failure in Europe and are totally unnecessary as CO2 has little effect on climate and the austerity measures will make absolutely no difference to future climates. If we have a second Obama administration, in 2016, we will look back at 2012 as the good old days. .

----------

In a nearly full-page op-ed appearing in the business section of the August 25 New York Times, Cornell professor Robert H. Frank lays out the new green agenda for tax policy.

According to Professor Frank, stopping global warming may require carbon taxes of about $300 per ton of carbon dioxide emitted, and by implementing such taxes, we can also balance the federal budget. “If such a tax were phased in,” Frank says, “the prices of goods would rise gradually in proportion to the amount of carbon dioxide their production or use entailed. The price of gasoline, for example, would slowly rise by somewhat less than $3 per gallon. Motorists in many countries already pay that much more than Americans do, and they seem to have adapted by driving substantially more efficient vehicles...many budget experts agree that federal budgets simply can’t be balanced with spending cuts alone. We’ll also need substantial additional revenue, most of which could be generated by a carbon tax.”

In addition to increasing the cost of American goods through carbon taxes, Frank recommends jacking up the price of imports through carbon tariffs, and he suggests that the U.S. government use such tariffs to force other nations to impose carbon taxes on their own citizens. “Some people argue that a carbon tax would do little good unless it were also adopted by China and other big polluters,” Frank says. It’s a fair point. But access to the American market is a potent bargaining chip. The United States could seek approval to tax imported goods in proportion to their carbon dioxide emissions if exporting countries failed to enact carbon taxes at home.

Let us consider the effects of this policy. A ton of carbon dioxide contains 248 kilograms of carbon, so a tax of $300 per ton of CO2 would be equivalent to taxing carbon at a rate of $1.21 per kg. Since there are about 2.5 kg of carbon in a gallon of gasoline, this would increase the cost of a gallon of gas by $3.02 per gallon, or just a little more than Frank says. The average American driver uses about 730 gallons of gasoline per year, so this tax would represent a cost of about $2,200 per driver. This would be a serious hit for the average American worker, whose before-tax income is about $45,000 per year, and devastating to those making less than this. But let us consider the effects on the economy as a whole.

The United States economy currently uses about 2.3 trillion kilograms of carbon per year, comprising 1 trillion kg in its coal, 0.8 trillion kg in its oil, and 0.5 trillion kg in its natural gas. Taxing this at Frank’s recommended rate of $1.21 per kg would therefore raise $2.78 trillion, somewhat more than the $2.3 trillion that the federal government raises through the current tax system (assuming that the carbon tax did not crash the economy, which it probably would, but we’ll leave that aside for now).

But what would the effect on prices be? Currently, western bituminous low-sulfur coal has a cost of $0.01 per kg at the mine, or $0.03 delivered to most users. Coal is about 90 percent carbon by weight. The green tax would thus multiply the cost of coal by nearly a factor of 40. A thousand cubic feet of natural gas contains about 18 kg of carbon. Taxing its carbon at a rate of $1.21 per kg would thus increase the price of a thousand cubic feet of natural gas from its current level of $2.50 to about $24.30, a tenfold increase. A barrel of oil contains about 110 kg of carbon. The green tax would thus hike the price Americans pay for oil by $133 per barrel over the world price (i.e., to about $230 per barrel today). As coal and natural gas provide the energy to produce not only the bulk of the nation’s electric power, but also most of its steel, aluminum, fertilizer, pesticides, food, plastics, electronics, glass, and many other products, and as oil provides the fuel to transport them, the cost of all of these would soar as well.

So who ends up paying? Under America’s current tax system, the top 5 percent of income earners pay 59 percent of all federal income taxes, the next 45 percent pay 39 percent, and the bottom half pays next to nothing. But because basic commodities such as food, electricity, and fuel are bought in similar amounts per capita regardless of income (i.e., a working-class family living on $30,000 per year in Harlem uses about the same amount of electricity and food as the family of a money manager living on $30 million per year on Park Avenue; and rural Americans, of whatever class, spend much more on gasoline than either), the $2.78 trillion green tax would be spread nearly evenly on all Americans, not as a fixed “flat tax” percentage of income, but as a fixed cost regardless of income.

Divided evenly among 300 million Americans, the green tax works out to a burden of $9,270 imposed on every man, woman, and child. While this would be a pittance for the most affluent Americans, it would take away 40 percent of the total income of a family of four supported by two wage earners making the average U.S. salary of $45,000 each, and it would be a virtually fatal burden for the poor.

The Obama campaign is currently banging the class-warfare drum, demanding that taxes on those making over $250,000 a year be raised by about 4 percent. Assuming no ill effects on the economy, this measure would raise $80 billion in revenue for the federal government, which conceivably might use as much as half of it, or $40 billion, in various programs that transfer part of their funds to lower-income people. “He pays less. You pay more,” say the president’s ads, promising largesse to the masses from the pockets of the rich. At the same time, however, green ideologues on whose ideas Obama’s energy policies are based are putting forth a proposal that would double the tax burden on the lower-earning 95 percent of the American public, with the poorest 50 percent being hit for a full $1.3 trillion of the increase.

But that’s not all. Because the green tax targets carbon, rather than income, it would act as a dirigiste economic policy favoring businesses that make money trading in paper instruments over those that produce real value through industry, agriculture, transport, mining, and construction. This would impoverish society overall, once again hurting the vulnerable the most, and would destroy tens of millions of blue-collar jobs.

Was ever a more regressive tax policy proposed? And has anyone ever demanded that the United States launch a trade war to force other countries to impose such oppressive policies on their own people, most of whom can afford them even less? There was a time when the Democratic party concerned itself with the needs of poor and working people. Alas, those times are past.

The green tax plan is a declaration of war on the poor.

- Dr. Robert Zubrin is president of Pioneer Astronautics, a fellow with the Center for Security Policy, and the author of Energy Victory: Winning the War on Terror by Breaking Free of Oil. His latest book, Merchants of Despair: Radical Environmentalists, Criminal Pseudo-Scientists, and the Fatal Cult of Antihumanism, was recently published by Encounter Books.

by Jorg Friedrich - 29.08.2012

Instead of welcoming critical discussion of complex scientific questions, we dismiss climate change skeptics as buffoons.

It was hot in Germany last week, very hot. But were the temperatures really “record-breaking”? Even before the heat wave had reached its apex, newspapers began to pose the question: how high, exactly, must temperatures climb before we can speak of “record heat"=? To find an answer, we must know how high temperatures have climbed in the past - a task that can be surprisingly complicated.

Temperatures are recorded in specific locations, and international guidelines for the recording process are well established. To determine whether a new temperature record has been broken, one must measure the temperature in a given location over a long period of time under stable conditions. One example: in Munster, a city in the Northwest of Germany, the thermometer recorded a temperature of 37.2 degrees Celsius at the city zoo last week, higher than ever before. The problem: during the previous heat wave in the summer of 2003 - when many weather stations in Germany recorded record-breaking measurements – no recordings were taken at that location. The old weather station at the zoo had been closed several years before when a more modern station opened twenty kilometers away at the airport, and the new private weather station didn’t exist yet.

Were temperature records broken or not?

We don’t know. Some scientists believe that the temperature records of the zoo are comparable to records from the airport, but a clear consensus doesn’t exist. The actual temperature in a given location is dependent on many local factors, whose respective influences fluctuate with wind direction, time of day, season, cloud cover, et cetera. To put it simply: it’s impossible to move a thermometer from one location to another one, measure the same temperature at both locations, and conclude that they will always be equally hot or cold.

This simple example points towards a big problem for climate scientists: temperature recordings over time and the calculation of means and trends are highly theoretical constructs that must take into account factors such as changes in measurement technologies, in urban development, and in vegetation near weather stations. The calculation of regional and global mean temperatures adds further complications: despite internationally agreed standards, measures are taken differently in different areas of the globe, and some areas are more densely dotted with weather stations than others.

In the past, scientists often had to rely on tree ring analysis and ice samples from glaciers to determine temperature levels in past centuries. Today, we use electronics and satellite technology to record meteorological parameters.

This shift alone illustrates how much observations must be supplemented by theories to produce nice and orderly temperature records.

Those who remain skeptical of scientists’ warnings of radical climate change often base their doubts on these theoretical constructions. That’s good. Doubt is what separates knowledge from belief. As paradoxical as it may sound, “knowledge” is something that can be doubted.

It’s not unusual that climate change skeptics still exist. What is unusual is that we tend to dismiss their doubts even in light of evident complexities in the reconstruction of past temperatures (which are barely comprehensible to a layman audience) instead of embracing them as the stirrings of enlightened reason, of man as he throws off the shackles of self-inflicted nonage.

Should we really believe grand scientific claims about atmospheric temperature change over the past decade if we cannot even determine whether temperature records were broken in a German city last week? Isn’t it normal to harbor doubts? Why should we believe scientists just like we believed priests in past centuries - as if they had access to secret knowledge, inaccessible to mere mortal.

---------

By the way, see under What’s New and Cool where the heat was followed by cold and even August snow